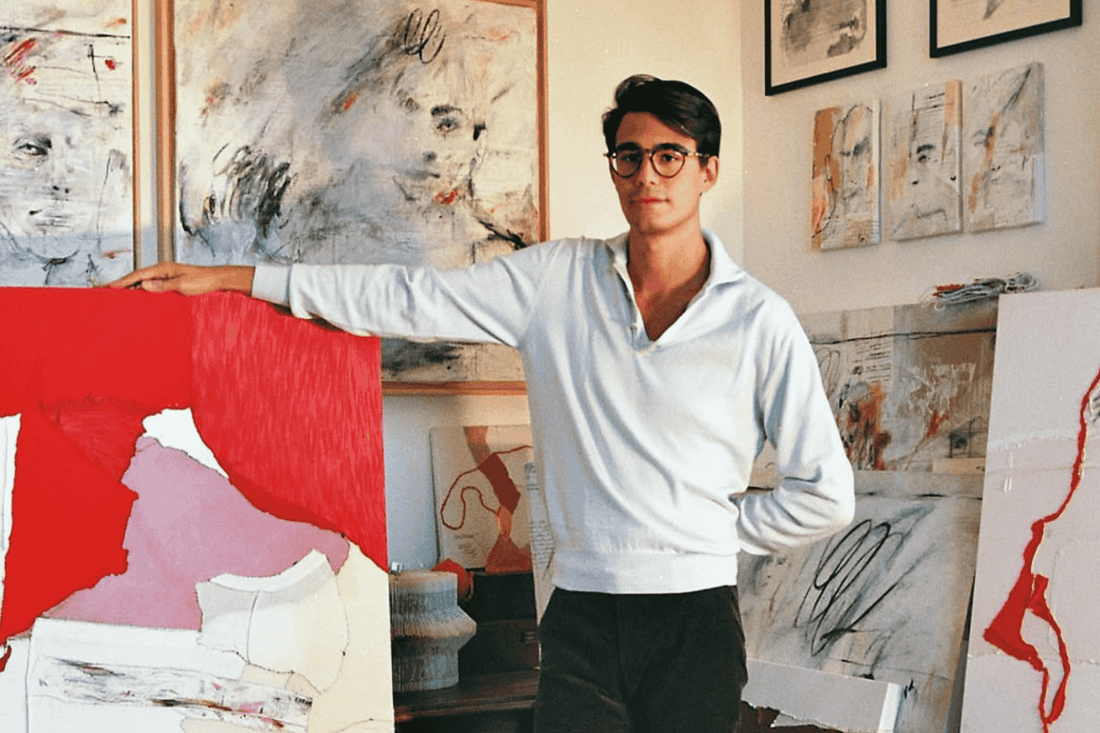

Modern Travellers, Eternal Poets: Roberto Maria Lino

Often artists create in stillness. But Roberto Lino moves, around the world and around his own poetic world. Not to escape, but to carry things: textures, memories, fragments of light.

Roberto is an artist whose work takes shape as he travels: folded, tucked and stitched. Fabric in suitcases. Memories in travel bags. And memories in the heart. But his way of doing is far from spectacle and far from the desire to be seen. He travels to remember, to absorb, and to continue a thread.

We invited him to join our series Modern Poets, Eternal Travellers, a portrait project dedicated to those whose experience of the world is measured in meaning.

"I try to take something from every place."

When we asked what a travel memory meant to him, he didn’t speak of photos or souvenirs in the conventional sense.

“It can be anything,” he said, “a book in a language I don’t understand, a broken shell, a stone. What matters is that it holds a fragment of that moment.”

Often, it’s film: images not yet developed, light captured on a roll. But just as often, it’s an object chosen intuitively, like the ceramic candle holders he found in a village in Morocco, or the shell from Yucatán that sits, now, like a fossil of emotion.

“Rome is warm.”

Rome by Roberto Maria Lino

Roberto’s Rome is a map of rituals. Of arrivals and departures, friends passing through, and quiet corners that hold entire seasons of memory.

There’s a toast at Bar Peru, curry chicken from Nino, a lamb cutlet at La Campana. There are films at the Giulio Cesare, gummy candies at the Adriano, the first blossoms at the Botanical Garden. The golden hour over Piazzetta Paradiso.

He speaks of spaces that aren’t just places, but moments. Like the courtyard of San Silvestro or the echo of instruments from the Conservatory of Santa Cecilia.

He knows where to find the city’s spolias. Where scenes from Conclave were shot. Where to look for the ghost of a scene from We All Loved Each Other So Much.

“Rome is a warm city,” he tells us. “And I like how people pass through it with wildly different passions.”

What Roberto brings in his bag when he travels

What he carries with him

His bag is its own archive. There’s a document holder from his mother. Glasses that belonged to his grandfather. A spool of red thread. A needle, just in case. Wired headphones, always tangled.

There are rolls of film, a camera, and never too much—only what’s essential to stay connected to who he is.

He never travels without these. Because travel, for him, isn’t about interruption. It’s a continuation. A long, slow unfolding of self.

“My grandmother let me try on her souvenirs.”

The most intimate memory he shares isn’t even from one of his own journeys. It’s from the stillness of childhood, when his parents were away and he stayed in the family home in Sant’Agata de’ Goti.

His grandmother had been everywhere: Perù, Russia, Polynesia. She had shell necklaces and fur hats, pareos and straw hats, and would let him try everything on. “Every time,” he remembers, “I would become a different character.”

Even now, he carries that same instinct: not to collect things, but to transform through them.

“I always travel with fabric.”

Roberto’s practice adapts to travel because it has to. Fabric folds. It carries things. It absorbs context.

In Egypt, where he recently developed a project on the Red Sea, he carries his materials in a suitcase, stretching them into new forms when he arrives. The same happened in New York, where his last solo show opened a few weeks ago.

It’s a way of working that doesn’t divide art from life. “Even when I’m far,” he says, “I remain connected to what I’m making. Because I bring it with me.”

Roberto Lino reminds us that to travel isn’t always to go far. Sometimes it’s to carry the right thing. To find a quiet space in a loud city. To remember what mattered.

To trace, again and again, the invisible threads between where we are and who we’re becoming.